OPB – Jeff Makes

On the campaign trail, Gov. Kate Brown and state Rep. Knute Buehler have settled into a predictable routine when asked about Oregon’s troubled public pension system, PERS.

Buehler, the Republican challenger, says he will prod legislators to cut retirement costs. He says that would free up hundreds of millions of dollars that could go into improving the state’s public schools.

“Too many dollars are not getting into the classroom,” Buehler said at a recent televised debate in Medford, Oregon. “They’re being diverted to retirement accounts.”

Brown, the Democratic incumbent, says she’s also working to reduce the pension system’s big debt. But on the campaign trail, she spends most of her time on the subject vowing to protect teachers and other public employees. She says they face big reductions in retirement benefits under Buehler’s proposals.

Oregon Gubernatorial Candidates On The Issues: Housing And Homelessness | Education | Immigration | Capital Punishment | Climate Change | Health Care

“I simply will not cut teacher retirement in order to fund schools,” Brown said at that Medford debate.

Oregon Gov. Kate Brown in the living room of Mahonia Hall, the governor’s official residence in Salem.

Julie Sabatier/OPB

Their divergent answers neatly display the political fault lines of one of Oregon’s thorniest financial issues.

Buehler gets much of his backing from business people who think it only makes sense to move to the kind of slimmer retirement accounts found in the private sector. And Brown is heavily backed by public employee unions worried about what will happen to their members’ benefits.

What is clear is that pressure is building to do something.

“I think it is an absolute necessity regardless of who is elected,” said Sen. Tim Knopp, R-Bend, who has long been involved in the issue. “They need to act as soon as possible.”

Overly generous pension payouts in the 1990s and early 2000s – as well as the nation’s financial crash in 2008 – helped drive a huge spike in the unfunded liability of the Oregon Public Employees Retirement System.

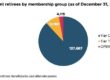

The system, which covers about 370,000 government retirees and workers, is now $22 billion in debt. That’s how much more will be owed to retirees versus what the system is actually collecting in rates from state and local governments and school districts.

That liability is driving ever-higher PERS rates. In 2009, public employers on average were charged just over 12 percent of a worker’s wages for the pension plan.

That rate has now zoomed up to 21 percent of salary. Next July, that rate will go up to 25 percent. Public agencies are expected to pay about $4 billion in rates, an increase of more than $1 billion over the two-year-budget period.

These rate hikes are increasingly forcing schools and other public agencies to shift money from other services to pay for higher retirement costs. So even as the strong economy adds money to the state budget, much of it can’t go to the services that Oregonians rely on.

Buehler is proposing several sweeping changes he hopes can capture as much as $1.2 billion in PERS savings in the 2019-21 budget. They include:

- Shifting some or all of the 6 percent public employees put into individual retirement accounts into shoring up the main pension plan. This would particularly hit younger workers who have not yet accumulated much in these accounts.

- For new employees, allowing only the first $100,000 of salary to be used to calculate pension benefits. This cap would be adjusted for inflation. But it could have a real effect on highly-skilled public workers, ranging from medical professionals to administrators.

- Shifting workers – particularly new employees —to 401k-style plans similar to those typically used by the private sector. Businesses like those plans because they don’t have a financial obligation to ensure that workers earn a certain level of benefits in retirement.

“I don’t want to take away benefits that people have already earned,” said Buehler. “But going forward, we need to reset that equation and expectations.”

Of course, Buehler could not take away previous benefits even if he wanted to. The Oregon Supreme Court has ruled that lawmakers can only reduce benefits for future work — not for past work.

But Buehler’s “reset” is much more dramatic than anything Brown has talked about.

Instead, the governor last year set up a task force she hoped would find ways to cut the system’s unfunded liability by $5 billion. Her big initiative out of that task force was legislation setting up incentives for state and local agencies to pay back their debt early.

She said she’s looking for spare cash to use as incentives. One example: When Comcast settled a big case with the state over how much the cable giant owes in property taxes, Brown pushed local officials to devote the money to paying down their PERS obligations.

In essence, it’s like encouraging homeowners to speed up repaying their mortgage to reduce interest costs. It is, she said, “the most rapid, the most effective way of bringing down employer rates.”

But Brown acknowledges that she is nowhere near meeting that goal of cutting the PERS debt by $5 billion.

“No, we aren’t,” she said.

Brown has also said she’s willing to look at PERS benefits. She praised a bill in the 2017 session that would have diverted a portion of the money going into those individual retirement accounts. Instead, it would go toward reducing the PERS deficit. She’s said public employees should “have some skin in the game” in helping solve the problem.

But the governor – and Democratic legislative leaders who floated that bill – said at the time that an agreement to raise additional revenue would have to be part of any deal on PERS benefits.

Brown also disagrees with Buehler’s attempt to move workers into a 401k-type plan. She noted that the Legislature already created a plan in 2003 for new employees that provides lower benefits. Already, most public employees are in the new system – and their plan only accounts for about 6 percent of the total PERS debt.

“I would argue that it is a very sustainable and affordable system,” said Brown.

It’s a persuasive argument for many public employees in the post-2003 system who think Buehler is unfairly gunning for their pensions to solve a problem created by previous generations.

“They’re trying to shoulder us with the biggest burden,” said Brandon Silence, a 36-year-old firefighter for the City of Salem, “and we’re the smallest fish in the pond.”

Former Oregon AFL-CIO president Tim Nesbitt said he understands the perspective of younger workers. But Nesbitt, who now consults on the PERS issue for the Oregon Business Council, said that public employers will find it increasingly hard to maintain services and provide pay raises if something isn’t done with PERS.

Even the slimmed-down pension provided to younger workers is still a generous plan, he said. Nesbitt said he was covered by this plan when he worked for state government from late 2006 to 2012.

“I earned better retirement benefits in those five years by far than in any five-year period working for unions,” he said.

For his part, Buehler said that in addition to shoring up schools and other services, he’s trying to protect younger workers who face pensions that could only be “worth pennies on the dollar.”

Buehler noted that the PERS debt could wind up being far above $22 billion. If investment returns don’t meet expectations, that liability could rapidly grow – and that’s when the state might not be able to meet its obligations.

The biggest question is how each candidate would approach PERS in the 2019 Legislature.

Buehler said he won’t sign bills for any new spending programs until legislators come up with an acceptable plan to reduce PERS costs.

Knopp, the GOP state senator, said that as governor, Buehler would have to negotiate a deal with a Legislature expected to remain in Democratic hands.

“It’s going to have to be a lot of give and take,” said Knopp, noting that Democrats would almost certainly insist on additional taxes in some form as their price for approving a PERS plan.

Buehler has been careful to give himself negotiating room on taxes. During the Republican primary, Buehler refused to take a pledge to avoid all tax increases. “I wouldn’t trust the Salem politicians with more taxes until they get the cost drivers under control,” he said at the time.

Brown said she thinks Buehler’s PERS proposals would be a non-starter in the Legislature.

“I think it’s unlikely that the Legislature, given its current makeup, would move forward on his proposal,” she said. “And I don’t think that threats and bluster get you anywhere.”

Perhaps the bigger question is whether Brown would expend serious political capital to drive down rising PERS rates. Several Democratic legislators privately say they are unsure what she would do if re-elected.

And many of her political allies are pushing her to focus on going after more tax revenue.

“We seem to be working on this premise that there can’t be new money in the system, and I think that’s a false premise,” said John Larson, president of the Oregon Education Association. The state’s powerful teachers union has endorsed Brown.

Larson decried the idea of reducing teacher benefits while large corporations in Oregon pay some of the lowest taxes in the country. “That’s not okay,” he said.

Still, both of Brown’s predecessors – Democratic Govs. John Kitzhaber and Ted Kulongoski – were willing to take on politically difficult legislative fights to reduce PERS costs. Kulongoski signed legislation in 2003 and Kitzhaber in 2013.

The state Supreme Court overturned many of those changes. For instance, it wouldn’t allow legislators to reduce cost-of-living raises for PERS retirees. But the changes that survived the legal fight did produce significant savings.

Brown is cagey about how far she’d go in trying to reach a deal on the pension system. But, she added, “my goal is to keep working to bring down employer rates because I totally understand that’s what drives more money into direct services.”